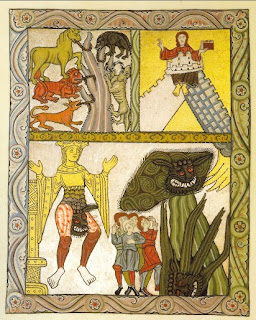

The allegorical figure of Ecclesia, the

virgin Holy Mother

Church, was one of

Hildegard of Bingen’s (1098-1179) most frequent visionary images. She appears

no less than five times in her first visionary work, Scivias, for which Hildegard later supervised the creation of a

deluxe illuminated manuscript, the Rupertsberg Codex. Though the original has

been lost since its evacuation to Dresden

in 1945, it survives in black-and-white photographs and a hand-executed

facsimile crafted by the nuns at the Abbey of St. Hildegard in the 1920’s, from

which the images that accompany today’s post come.[1] The visual

images of Ecclesia in this manuscript are vast, powerful, and often extraordinarily

hybridized, with a variety of non-human elements grafted on, each with its own

allegorical significance. Sometimes, as in the image for Scivias II.5 (Fig. 1), of the virginal orders of her mystical body,

the monumental quality of flaming gold wings rising from Ecclesia’s shoulders

and of the silver mountains comprising her lower body inspires awesome wonder.

|

| Figure 1 |

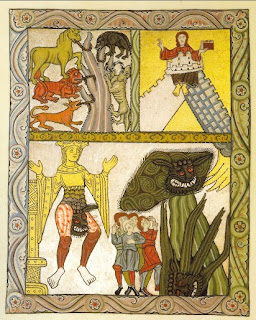

There is another image of Ecclesia, however, that is gruesome and disturbing—her rape by the Antichrist in Scivias III.11 (Fig. 2). Hildegard describes her (e)sc(h)atological vision of the last days:

And I saw again

the figure of a woman whom I had previously seen in front of the altar that

stands before the eyes of God; she stood in the same place, but now I saw her

from the waist down. And from her waist to the place that denotes the female,

she had various scaly blemishes; and in that latter place was a black and

monstrous head. It had fiery eyes, and ears like an ass’, and nostrils and

mouth like a lion’s; it opened wide its jowls and terribly clashed its horrible

iron-colored teeth. (…) And behold! That monstrous head moved from its place

with such a great shock that the figure of the woman was shaken through all her

limbs. And a great mass of excrement adhered to the head; and it raised itself

up upon a mountain and tried to ascend the height of Heaven. And behold, there

came suddenly a thunderbolt, which struck that head with such great force that

it fell from the mountain and yielded up its spirit in death. And a reeking

cloud enveloped the whole mountain, which wrapped the head in such filth that

the people who stood by were thrown into the greatest terror.[2]

|

| Figure 2 |

Appearing in the lower register of the

image, Ecclesia’s upper body is the golden orans figure familiar from earlier

in the manuscript. Her lower body, however, has been replaced with a brutal

assortment of bruising reds and scaly browns, capped with the monstrous and

grotesque head of the Antichrist leering out from her genitals, his phallic ear

erect for penetration. Such grotesque hybrids become common in the marginal art

of gothic manuscripts, where the gryllus, for example, in the lower margin of

Psalm 101 in the Ormesby Psalter (Fig. 3) might seem to echo the genital mask

in Hildegard’s image. Indeed, the little prayer-book of Marguerite that Michael

Camille examined in his seminal Image on

the Edge offers a telling comparison: a woman’s book whose pages “are

pregnant in the sense that they teem with gynaecological promise even within

the detritus of fallen, decomposing life.”[3] There is, however, a

crucial difference between Marguerite’s prayer-book and Hildegard’s Scivias: far from being on the margins,

Hildegard’s Antichrist is found at the very center of the Church, inside her,

taking over her womb and thus corrupting her mission: “I must conceive and give

birth!” (as she announces in Hildegard’s vision of the Church and Baptism in Scivias II.3).

|

| Figure 3 |

Hildegard describes this violent hybridized

rape as the consequence of “fornication and murder and rapine” committed by

Ecclesia’s own ministers, their “vile lust and shameful blasphemy (…) infused”

in them by the Antichrist’s “voracious and gaping jaws” (Scivias III.11.12-13). Madeline Caviness has suggested that

Hildegard’s radical alteration of “existing iconographic codes” in this image

was so threatening as to render it obsolete from successive periods of medieval

art, yet provocatively resonant “with numerous self-images of contemporary

feminist artists, who fragment and mask their bodies to repel the male gaze.”[4]

Richard Emerson, likewise, finds the visual image to be far more radical and

disturbing than the mostly conventional account of the Antichrist offered in

the vision’s commentary (Scivias

III.11.25-40), whose innovations can be understood as the product of the

conventionally symbolic exegetical imagination of twelfth-century monastics.[5]

One of Hildegard’s extraordinary contributions to the Antichrist tradition is

to portray the fiend as a sexual subversive and criminal—and to move that

subversion from the margins into the very heart and womb of Mother Church

herself.

-Contributed by Nathaniel Campbell

Notes

[2]

Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, trans.

Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (Paulist Press, 1990).

[3]

Michael Camille, Image on the Edge: The

Margins of Medieval Art (Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 54.

[4]

Madeline Caviness, “Artist: ‘To See, Hear, and Know All at Once’,” in Voice

of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World, ed. Barbara Newman

(University of California Press, 1998), pp. 110-124, at 117-8.

[5]

Richard K. Emmerson, “The Representation of Antichrist in Hildegard of Bingen’s

Scivias: Image, Word, Commentary, and

Visionary Experience,” Gesta 41:2

(2002), pp. 95-110.

Images

Fig. 1: Scivias II.5: The Orders of the Church

(Ecclesia). Facs. of Hessische Landesbibliothek, MS 1 (Rupertsberg Codex,

lost), fol. 66r. Source: Abbey

of St. Hildegard

Fig. 2: Scivias III.11: The Five Ages and the

Antichrist born of the Church. Facs. of Hessische Landesbibliothek, MS 1

(Rupertsberg Codex, lost), fol. 214v. Source: Abbey

of St. Hildegard

Fig. 3: Gryllus,

in detail from lower margin of Ormesby Psalter, Ps. 101: Bodleian Library, MS Douce 366, fol. 131r. Source: Bodleian

Library